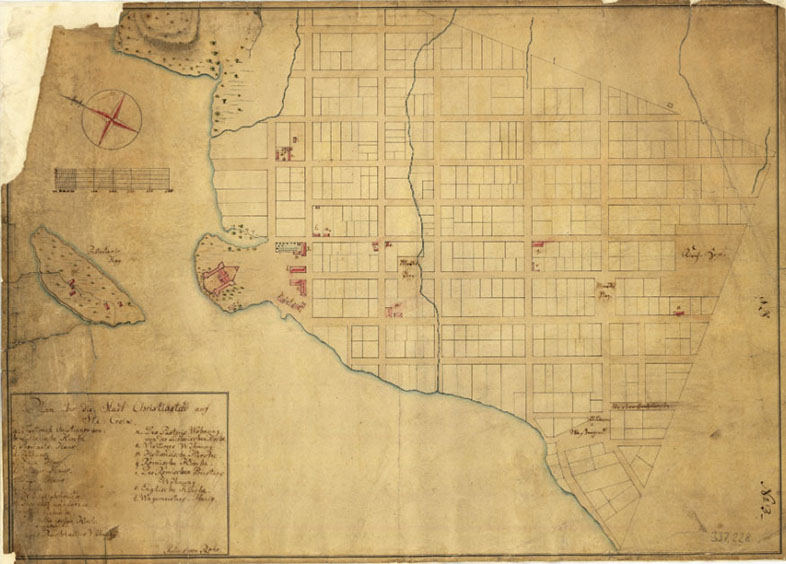

Julius von Rohr (1735-1793), became a surveyor in the Danish West Indies in 1757 at the young age of 22. He created two maps of Christiansted which predate the Oxholm map of 1778-1780. These two maps which the Danish Archive number as 337.216 and 337.228, were among his first products.

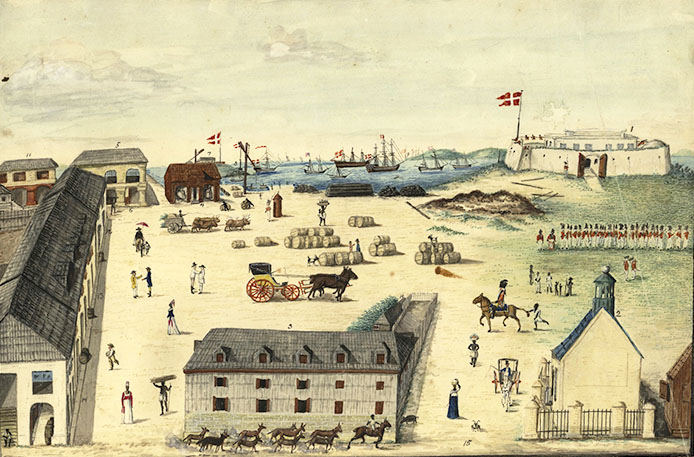

Of notable difference compared to the Oxholm map is that there are no walls defining the Danish West India Guinea Company material yard. The Fort and Steeple Building are clearly identified, as are the two Company warehouses, so these maps can be used to approximately date this painting of the wharf area which also shows the Fort, Steeple Building and company warehouses. So the walls of the material yard were built some 18 to 20 years later.

Julius von Rohr, an Enlightenment scientist of the colonial Atlantic

According to Daniel Hopkins1

Julius von Rohr, a German immigrant to Denmark, was appointed municipal buildings inspector and government land surveyor of the Danish West Indies (now the United States Virgin Islands) in 1757. At the same time, he was commissioned by the Danish crown to study the natural history of the islands, and botany was his particular passion. He established a botanic garden on the island of St. Croix and corresponded with major figures of natural history in Denmark and elsewhere. In the 1780s, he made an agronomical study of cotton cultivation all along the length of the Antilles, traveling as far as Cayenne and Cartagena. In the 1790s, when Denmark’s abolition of the Atlantic slave trade was imminent–a measure which was expected to doom the rich sugar plantations of the Danish West Indies–the government asked von Rohr, who by this time, besides his scientific expertise in the tropics, had more than thirty years’ colonial administrative experience, to undertake an expedition to assess the potential of the territory around the old Danish slaving forts on the West African coast for plantation agriculture. He sent ahead of him surveying instruments and a substantial little library, the catalog of whose titles is highly indicative of his colonial concerns. Von Rohr traveled by way of the United States, where he hobnobbed with prominent politicians and natural historians in Philadelphia and New York. The Danish government’s reliance on a West Indian scientist in its ambitious new African colonial venture brings out the importance of natural history in colonialism and underlines the economic and geographical coherence of the Atlantic plantation world in the minds of high-ranking European policy-makers. The economic model of the West Indian plantation was central in European speculations and projects for the African tropics at the turn of the nineteenth century. Von Rohr’s errand came to an abrupt end, however, for the ship carrying him to Africa from New York vanished in the Atlantic.

Botanist Benjamin Smith Barton, though, declared that he did make the voyage safely, but died of fever shortly after:

“….my friend the late Mr. Julius von Rohr, a gentleman whose death is a real loss to natural science, and perhaps an irreparable loss to the interests of an injured and oppressed part of mankind: I mean the Blacks. In the summer of 1793, I took my last adieu of this learned botanist, and most amiable man. He sailed, from New York, for the coast of Africa, where he contemplated the establishment of a colony of Blacks. A few days after he had landed on the African continent, he died of a malignant fever. With him, I fear, has perished, for a long time at least, one of the best concerted schemes for the safe and happy emancipation of the swarthy children of Africa. Von Rohr was another Howard. In benevolence and good sense, he was, at least, equal to the great English philanthropist. In science certainly, and perhaps in the simplicity of his conduct, and the unambitious fervour of his zeal, he was the superior”.

The exact location of von Rohr’s botanical garden within Christiansted is not well-documented in historical records. Given his role as a municipal buildings inspector and government land surveyor, it’s plausible that the garden was situated near the administrative or commercial centers of Christiansted, possibly close to the harbor area where he conducted much of his work. Today, the St. George Village Botanical Garden (not associated with Rohr’s garden) showcases a diverse collection of native and exotic plant species.